Below is a guest blog, written by Rhumba's outreach director, Erica Rabner.

An Introduction to Binaural Technology: The Future of Children’s Podcasting

Last week I hung out with Nathaniel Reichman (Supervising Producer – Re-recording Mixer at Rhumba and Dubway) and John Bowen (Sound Supervisor | ADR Supervisor | Music Editor) to talk binaural audio and other buzzwords I’ve been hearing around the studio. I learned about the important role immersive audio plays in storytelling. Nat and John told stories and unpacked techniques and processes behind kids shows and podcasts that help immerse kids in the story.

Before we get started: what is 3D audio?

JB: 3D Audio approximates what you hear in real life. When something is behind you, you hear it slightly differently than when it’s in front of you. Binaural is a type of 3D audio that uses only 2 channels (one for each ear), and it’s been around for more than a century. It was never very popular, because recording required specialized equipment that was cumbersome and limiting. What’s new about what we've been doing, is we’re finally able to create a binaural effect using computer processing.

Now let’s break it down one step further: how would you describe binaural to a preschooler?

NR: Kids should be encouraged to close their eyes, and answer, “can you hear my voice above you, below you, in front?” “Why does it sound different when something’s in front/behind? Think about that...” Not only are kids learning the nuances of binaural recording, but this exercise serves as a great way to explore one of the most important senses: hearing!

I’d heard about using a dummy head in a New York Times piece about children’s podcasting. NYT described the binaural recording system as:

“a mold of a human head outfitted with microphones — to create a 3-D listening experience that feels unlike anything children can read or watch” (Hess, 2017)

Sounds old school, right? Well JB and NR did mention that binaural has been around for a long time - think 1881! HOWEVER, thanks to technology, we’ve upgraded. Now we don’t need to record using a dummy head; instead, engineers can tinker and manipulate information with their computers to yield the same results.

JB: Dolby Atmos has modeled what the head hears for any point in the 3D area of your head so that you don’t have to record with a head to get the effect that something is around you or behind you. There are lots of different models to account for differences in the way people’s ears work, size of head, etc.

NR: When we hear something, we hear it with two ears but the shape of your face and mask of your head creates a filter. HRTF, Head Related Transfer Function, considers how your head affects sound when it arrives at your ears.

With Dolby Atmos, engineers can use a software model of the HRTF in post, which creates the difference of what the right and left ear hear based on what’s between them. Way to go, technology!

As Nat pointed out, both methods have strengths and weaknesses:

DUMMY: When recording with a dummy head, you have to position your actors precisely where you want them in 3D space, and once recorded, you can’t change that in post. “You need to choreograph the scene around the head which takes a tremendous amount of pre-production.” – JB “If you’re recording with a dummy head, you can’t do pick-ups. If the actor is standing in a slightly different spot, the sound will jump around your head in an unpleasant way.” – NR

DOLBY: With synthetic/binaural software, everything can be done in post-production. You can take a normal mono recording and place it anywhere around someone’s head. You can move it in 3D space and manipulate the spatial quality.

So now that we’re all on the same page...why use binaural?

NR: Binaural helps tell a story better. You’re given context on the screen i.e. if two people are talking in a gym, you see them there and your mind expects you to hear them there. These are more than fancy tools to play with -- in an audio only experience, it’s critical to have these tools to make the story compelling.

JB: Virtual reality increases your empathy with the story being told; the same is true with 3D audio in an audio-only program. When it seems more realistic, you feel more invested in what the characters are feeling.

“When it seems more realistic, you feel more invested in what the characters are feeling.”

What’s it like exploring a new medium?

JB: We’re in an experimental phase – anything goes right now – which is extremely exciting.

NR: We’re developing a new language now. When reality TV was starting out, they hadn’t developed their visual language, so it was hard to watch. Along the way, they found ways to show things they were having trouble with. Once a new language was developed, things started making sense.

How does audio-only differ from audio with picture?

NR: 3D audio tools help us to compensate for all the information you’re not getting when there’s nothing to look at. You can make a pretty good story with standard stereo, but if you want it to be great, you’ll want to use binaural/3D audio. There’s that old joke that TV without picture is radio, but TV without sound is broken.

JB: In a podcast, you know you’re going it alone with audio, so you approach cutting and storytelling in a way that will work completely on its own. The sound is the only thing that's telling the story. In TV and movies, the dialogue is generally the most important part of the sound because you know the picture can do much of the heavy lifting in other storytelling areas.

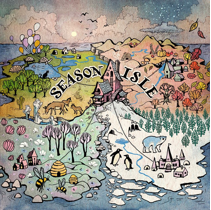

I asked Nat and John to talk about "Season Isle,” a unique podcast for Pinna that takes advantage of 3D audio:

NR: In Season Isle, it’s really important to communicate location. Each of the four seasons have their own sound, and it was important to communicate which season we were in without relying on dialogue. 3D binaural allowed us to put people in places and keep them separate. With a non-visual medium as soon as you have more than three actors it gets tricky -- the binaural experience helps you locate them and keep the story straight.

JB: Sometimes, we’d have scenes with five or six characters, so we would set them up across the spectrum from each other, and you’d be able to tell who everyone was – largely by where they were located in space. Dolby makes a huge difference when panning – ‘placing’ is probably a better word for it. You can put a character in the upper right, another slightly behind you, three on your right talking to two on your left. The pinpointing of location of Dolby Atmos is so precise, I can make characters sound like they’re walking – you feel motion just from minute changes in location.

NR: It feels like you’re next to that person and in that space. It’s the complete opposite of an actor in sound booth who has been instructed to stay still on the mic.

JB: Nuances – direction of motion, where people were located with relation to other things – were important to the story. We actually had the director draw us a series of maps so that we could know if we were in ‘Spring’, ‘Winter’ is over there, and we’d have to fly left.

How can you convey what a place looks and feels like without picture?

“Sometimes you don’t need to see it to feel it”

JB: Say a character is standing on a dam looking out over a wide valley. We want the listener to feel that expansive setting. I might start by taking something like a bird, putting it in the distance – small, and making it echo in a way that the listener’s mind automatically envisions the scope of the scene. There are archetype clues -- we have a sound language for things. Sometimes you don’t need to see it to feel it. Music helps, too – a good composer can be worth a lot in this space.

NR: When children learn, they develop associations between what they see and what they hear in the real world. Binaural tools let us use those associations to create imaginary audio worlds. We’re using the HRTF to give clues. Where am I standing? Is it a big place?

What questions should producers be asking about binaural audio?

NR: They should be asking to come to the studios. Come to us for demos. They need to start hearing the format to find out where the boundaries are. The goal posts have moved, and you have to play with it to understand what can be done.

JB: “How can we use this to do what we have to do more effectively?” We are creating a bunch of new sound conventions, just by solving problems using these new tools. You can hear all the decisions that were made along the way. i.e. I’ve got three characters -- one’s hang gliding, and the others are on the ground. There are cool ways to solve that problem. Maybe you have a group of donkeys, one’s caught in a whirlwind hurricane, the others are watching from a cave. You could show that in 3D by placing the characters on the right in an echoey cave, then placing the whirlwind in the distance with a donkey on the left. Binaural allows us to keep these elements separate and make sense of it all from a spatial perspective.

“IMMERSIVE IS THE FUTURE”

Is binaural the future?

JB: It’s definitely part of it.

NR: I would say immersive is the future and that we can scale it up and down. The future is scalability. I can listen with my whole family in Atmos or surround sound and later put on my headphones and have an immersive experience in different venues. The new TV format, “Next Gen TV” lists immersive audio as part of the spec. All of our TV mixes will be immersive in the future. It’s great to start early in the immersive formats so when you switch to “Next Gen TV”, you’re already rocking.

1 Feret, Q. “Binaural Audio: How 3D audio hacks your brain.” AR VR Journey, October 20, 2017.

2 Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site. http://cnx.org/content/col11496/1.6/, June 19, 2013.

Hess, A. "The New Bedtime Story Is a Podcast." The New York Times. 3 Oct. 2017. <https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/03/arts/kids-podcast-panoply-pinna.html>.